The Road Full of Challenges – When Hymns Are to Be Sung in Cantonese

I shared in previous blogs that hymn lyrics are worth retranslating for Cantonese-speaking Christians, even though we already have Chinese versions of those hymns (people of different dialects read the same Chinese characters). I have proposed biblical foundations for singing tone-matching lyrics, which is crucial if we care for the dissemination and transmission of hymns (non-believers are more familiar with Cantopops, which are in Cantonese with tone-matching lyrics). They naturally find dissonant lyrics with melody unfamiliar, even comical. More importantly, they may not be able to fully grasp the meaning of the lyrics by merely singing or listening to the hymns, and it is not easy to memorize these lyrics. However, retranslating these hymns also brings numerous challenges. Not everyone will accept and embrace it entirely, or even consider it a positive thing.

The New Youth Hymns

Several years ago, I was involved in translating the New Youth Hymns, a project by the Christian & Missionary Alliance Church Union Hong Kong. This project aimed to retranslate the lyrics to tone-matching Cantonese and rearrange the accompaniment of 60 classic hymns for the praise teams to pass on the hymn singing tradition to the newer generations within our denomination. The 60 hymns were selected and published in four songbooks and CDs within a few years. When the retranslated hymns were distributed for singing, some pastors and brothers and sisters commented that the new lyrics were not as literary as the old ones. This may have been partly because their familiar versions had been replaced. They felt a complete overhaul that caused emotional distress. In fact, because of the need to follow the melodic design and the meaning of the original lyrics, the translated lyrics could not be as easily expressed as free writing. However, dedicated colleagues still painstakingly translated the original meaning while also fitting the lyric’s tones with the music’s melodies. Achieving this would be a win-win-win situation: melody, lyrics, and tone could work together seamlessly.

In the Congregational Setting

During my pastoral work more than 10 years ago, I occasionally tried to introduce the congregation to sing some of the retranslated hymns. Some brothers and sisters expressed that any alterations to the Hymns of Life, our denominational hymnal, were unacceptable, as if someone had damaged the Mona Lisa by adding a stroke to it. Some song leaders even stated that they would not lead singing if they had to sing newly translated lyrics (and I did not force them to sing the new lyrics). However, no single translation can be considered the only version on this planet, because it’s not original: it is simply a translation. I can understand that, since the brothers and sisters have long sung the Hymn of Life version as their only version, it will be very hard for them to sing any other version of it. The case is much like the introduction of newer Bible translations when people have memorized a typical version for a long time. So, the brothers and sisters’ inability to accept the re-translation is more based on subjective emotional factors than rational and objective analysis. Of course, it is also true that not every new translation is of equally high quality, but time will tell.

During my pastoral work more than 10 years ago, I occasionally tried to introduce the congregation to sing some of the retranslated hymns. Some brothers and sisters expressed that any alterations to the Hymns of Life, our denominational hymnal, were unacceptable, as if someone had damaged the Mona Lisa by adding a stroke to it. Some song leaders even stated that they would not lead singing if they had to sing newly translated lyrics (and I did not force them to sing the new lyrics). However, no single translation can be considered the only version on this planet, because it’s not original: it is simply a translation. I can understand that, since the brothers and sisters have long sung the Hymn of Life version as their only version, it will be very hard for them to sing any other version of it. The case is much like the introduction of newer Bible translations when people have memorized a typical version for a long time. So, the brothers and sisters’ inability to accept the re-translation is more based on subjective emotional factors than rational and objective analysis. Of course, it is also true that not every new translation is of equally high quality, but time will tell.

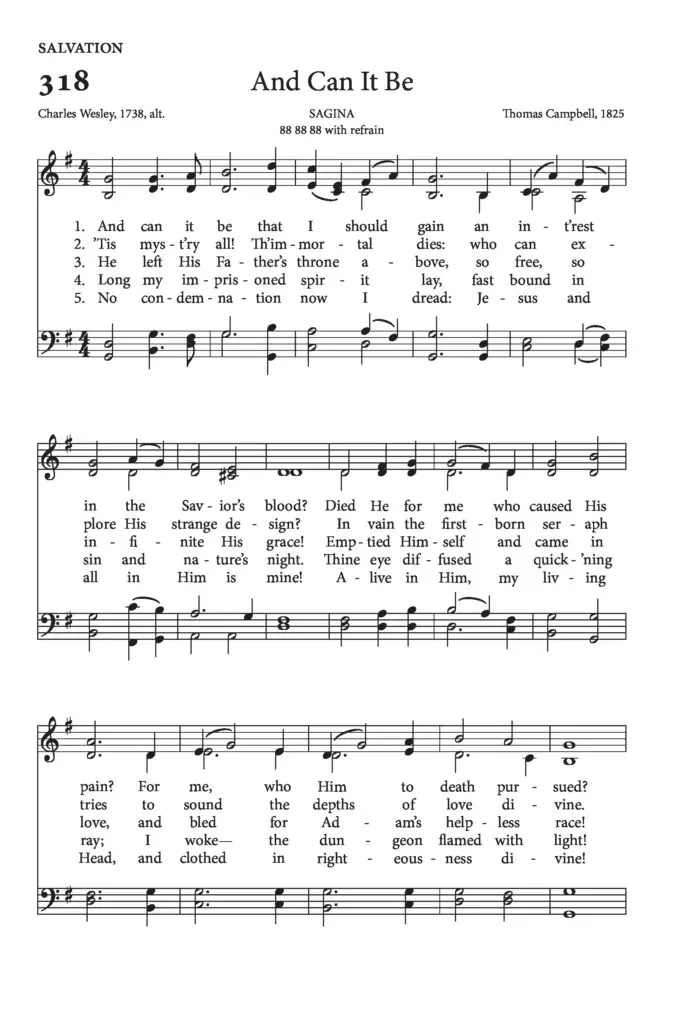

Original “And Can It Be” text and tune

In the past week, I encountered a rather serious problem when my church chose the retranslated version of “And Can It Be That I Should Gain” (lyrics by Charles Wesley, tune by Thomas Campbell) as our opening hymn. The original version had multiple musical notes per syllable, but in Cantonese, with its tones, this is not the ideal way to express the lyrics. Therefore, the translator of this hymn decided to assign each character to a single note, much like how we handle Cantopops in our culture. While remaining faithful to the original lyrics, this approach does significantly differ from the original version in terms of singing. The organist suggested that the congregation should have some prior rehearsal of singing this hymn version, at least to let them know it was a different version. However, the pastor felt it was not necessary; the choir could sing the first verse once and the congregation would get it. As a result, most people were unable to sing the hymn.

Coincidentally, I was teaching Sunday school on topics relating to hymns and spiritual growth during this period at my church. After class, a student told me that she could not sing “And Can It Be That I Should Gain” at all during worship that day. She felt very frustrated and confused and asked me if there was something wrong with her. I replied that I understood this was a common experience for many people. The original hymn is so deeply ingrained in people’s minds that they have memorized it thoroughly. So, without any warning, a completely new version is introduced—not just different in the lyrics, but also in the singing style. In the phrase before the refrain, each musical note has a different Chinese character, which can indeed leave some people familiar with the original hymn feeling helpless. In particular, since the projection only shows the lyrics without any melody cues, people may wonder how they can sing the melody with so many words. It is truly difficult to master. Of course, I also told her why this version existed. I said that it was possible that in our community, when singing the old version before, the lack of harmonies meant the lyrics were not deeply understood or were even just parroted. However, because of this tone-fitting version, the lyrics could finally be heard by the singers, and our brothers and sisters could clearly and vividly hear the truths of imprisonment, the liberation from the chains, etc., and may therefore felt moved and grateful. This shows the diversity in our community. Because of mutual love and consideration for edifying others, even if we have a version we are already very familiar with, can we also wholeheartedly learn how to sing the new version, and even treating it as a new song to learn, so that the next time we have the opportunity to sing it, we will be more engaged and able to appreciate the communion, inclusion, and richness it brings?

Conclusion

Compared to our brothers and sisters in the English-speaking world, we do indeed encounter more complex situations when it comes to singing hymns. The church music pastors and leaders can surely help in this process by carefully attending to the congregation’s expectations and capacity, tailoring the needed preparation for specific hymns, and thoughtfully explaining the purpose of the new version to the congregation. This understanding and acceptance will reflect the beautiful sentiment of putting aside our own comfort zone and preferences for others, singing God’s glory in the most natural and meaningful way in the language God has given us. Even if it comes at a high price, it is worth it. May God receive the highest glory and praise because of what we sing and do!

In case you have missed my previous blogs on Cantonese Hymn Singing, you can find them here: Part I of V, and Part II of V, and Part III of V, and Part IV of V, and Part V of V.

Blogger Yvette Lau has bachelor degrees in Chinese and Translation, and Music, a Master in Worship, and a Doctor of Pastoral Music. She has served as one of the executive committee members of the Hong Kong Hymn Society from 2011-2017. Her passion lies in choral conducting, song writing, hymn translation from English to Cantonese (main translator for New Youth Hymns), event organization, translation of books on worship including The Art of Worship, Beyond the Worship Wars, The Worship Architect, and Glory to God, and training and teaching on worship.

Blogger Yvette Lau has bachelor degrees in Chinese and Translation, and Music, a Master in Worship, and a Doctor of Pastoral Music. She has served as one of the executive committee members of the Hong Kong Hymn Society from 2011-2017. Her passion lies in choral conducting, song writing, hymn translation from English to Cantonese (main translator for New Youth Hymns), event organization, translation of books on worship including The Art of Worship, Beyond the Worship Wars, The Worship Architect, and Glory to God, and training and teaching on worship.