A Tale of Two Melodies – When Hymns Are to Be Sung in Cantonese

(Part II of V: The Technical Problems)

Changes in Time

In recent missiology, in the context of presenting the gospel message or implementing liturgical actions for a tribe or group of people, the term “heart language” refers to a group’s mother tongue or the dialect closest to their hearts. For us Cantonese speakers, our mother tongue language, spoken by the vast majority of the Hong Kong people, is a tonal language.[i] In the early years of the last century, missionaries served primarily in the mainland, and their serving partners and target groups were mainly people speaking Mandarin and other dialects. Therefore, it was not surprising to find that honoring the tonal nature of Cantonese was not a main concern for early hymn translation work. In spite of this, the Holy Spirit has continually blessed the hymns translated by the missionaries, and generations of believers have been nourished spiritually by those translated hymns.

Undoubtedly, those missionaries who came in those early days had given great effort to share their beautiful and life-enriching hymns to the Chinese churches. When Cantopop began to flourish in the 1970s, the new generation became “Cantopop natives”–that is, the first generation who had never experienced a time when there was no Cantopop in their lives.[ii] This is important because all Cantopop songs honor the tonal changes in the lyrics when they are being put into the melody. Cantopop natives (and also other non-church-goers) may perceive the older translated hymns as different from local music, and even strange or funny to listen to. In some extreme cases, the lyrics may even sound like foul language. In addition, waves of Praise and Worship music washed all over this generation in the 80s and 90s. In time, all these tides converged into a river. Now is an optimal time for us to seriously reflect on the present situation and the opportunity of congregational singing, and rethink what mission God has given to this generation of Cantonese-speaking believers.

Cantonese Tones and Musical Melody

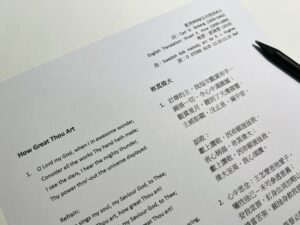

When a musical melody meets Cantonese tones, usually conflicting situations will arise between the music and the text. This is because the music itself already has a melody. However, Cantonese text with definite meaning also has its own “melody.” For example, if you want to say “旋律遇上粵音” (when a melody meets Cantonese tones), you are already naturally singing in the melody of “do so mi fa mi so.” Most Cantonese songs are composed with the melody first, followed by the lyrics; seldom would one find the lyrics written first, followed by the melody. Translating songs is in fact more difficult than writing lyrics for a melody because both the musical melody and the meaning of the lyrics have already been determined. If, at the same time, one also needs to deal with the Cantonese tones, it means that he or she will need to consider all three aspects simultaneously: melody of the music, meaning of the lyrics, and Cantonese tones and to achieve harmony between the two melodies. This is like dancing with chains indeed.

For those of us whose mother tongue is Cantonese, if we want to follow the practice of the music serving the lyrics, we would unquestionably encounter some difficulties. Hymns translated without being aware of the conflicting nature of the “two melodies” could be subject to ridicule from unbelievers (and possibly believers), as this is not what is found in Cantonese songs in our culture. However, sometimes it is not the translation that causes the difficulty, but the fact that we have sung hymns or praise and worship songs originally written for Mandarin. If we sing these songs in Cantonese, the tones and melodies largely conflict with each other. Strangely enough, since songs with non-matching Cantonese tones have been used for so many years in the churches, church songs that do not reflect or honor the Cantonese tones have defined the style of local church music in the minds of many even in the wider culture.

(In case you have missed Part I, you can find it here: https://congregationalsong.org/a-tale-of-two-melodies-part-i/)

Blogger Yvette Lau has bachelor degrees in Chinese Translation and Music, a Masters in Worship, and is now pursuing a Doctor of Pastoral Music. She has served as one of the executive committee members of the Hong Kong Hymn Society from 2011-2017. Her passion lies in choral conducting, song writing, hymn translation from English to Cantonese (main translator for New Youth Hymns), event organization, translation of books on worship including The Art of Worship, Beyond the Worship Wars, The Worship Architect, and Glory to God, and training and teaching on worship.

Blogger Yvette Lau has bachelor degrees in Chinese Translation and Music, a Masters in Worship, and is now pursuing a Doctor of Pastoral Music. She has served as one of the executive committee members of the Hong Kong Hymn Society from 2011-2017. Her passion lies in choral conducting, song writing, hymn translation from English to Cantonese (main translator for New Youth Hymns), event organization, translation of books on worship including The Art of Worship, Beyond the Worship Wars, The Worship Architect, and Glory to God, and training and teaching on worship.

[i] Cantonese is a tonal language with six phonetic tones. The relationship of the tones is relative but not absolute and to certain extent, the tonal quality is crucial for speaking Cantonese accurately. For more information on Cantonese, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantonese

[ii] Cantopop (or HK-pop) is a genre of pop music written in standard Chinese and sung in Cantonese. For more information of Cantopop, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantopop

Great article! I learned a lot from it because I am culturally American. I would think the translation of the lyrics would direct the tune, and that the tune that goes beyond lyrics should consistent harmonically with the Cantonese lyrics. I suspect the tunes derived from the lyrics could make for some wonderful new tunes! Thank you for writing this. (Jimmy Sham sent me the link to your article.)

Hi David, thank you for your feedback and sharing. In our culture, most of the lyrics are written after the tune is composed because that will make sure the songs are more singable and beautiful! When I compose new songs, I have tired to write the lyrics and the tune simultaneously so that the result will be more desirable and controllable! Thank you for your sharing of thoughts! (Jimmy is a dear brother in Christ!)