The Sunday Soundtrack

If you had to make a list of approximately 40 songs that best characterize your church, which songs would you choose?

Here’s the catch: I’m not just referring to your local congregation. Spring and summer tend to mark the season of national “conventions,” “assemblies,” “conferences,” and “synods” for churches of all denominations. It is a time when representatives of local congregations come together to make decisions as a wider community of faith. It is an opportunity to celebrate what we share with other congregations and to remind us that we can still diverge on matters like music even if we belong to the same denomination. How do we sing together at these national events when the Sunday morning soundtrack varies so much from one congregation to the next?

I have been asking these questions for months in relation to my own denomination. A few weeks ago, I served as one of the worship leaders at Mennonite Church Canada’s national “gathering” (because “synod” or “convention” would sound a little too formal for us) in Kitchener, Ontario. My role included curating approximately 40 songs for 400 people of various theological perspectives and social locations to sing together in a high school gymnasium. This year, to further increase the stakes, we also recognized the 500th anniversary of the birth of the Anabaptist movement in Europe (from which the Mennonite tradition emerged) while we simultaneously attempted to deconstruct Western narratives that have dominated our church’s landscape and undermined intercultural expressions of faith. Although we are a predominantly white denomination with a strong (and rather ethnocentric) attachment to strophic hymns with four-part harmonies (McCabe Juhnke 2017; Johnson and Loepp Thiessen 2023, 221–22), our demographics are shifting, so our denominational leaders made a point of inviting BIPOC speakers and encouraging ways of worship that would be representative of our predominantly BIPOC congregations.

The Stats

It is no small task to discern what to sing at an event that keeps returning to the theme of an “intercultural church in the womb,” to quote one of the event speakers. In fact, it was the most emotionally demanding gig that I have encountered in my church music career thus far. Together with my fellow committee members, I saw it as a delicate balance of choosing songs that would reinforce, expand, and challenge our identity as Mennonite Church Canada. In the end, our “Billboard Top 40” (which we narrowed to 35 songs) took the following statistical form:

- 26 (74%) songs were sourced from our denominational hymnal, Voices Together

- 13 (37%) songs included vocal harmonies

- 9 (26%) songs were connected to a BIPOC individual or community and/or were sung in a language other than English

- 8 (23%) songs would qualify as contemporary worship music

As a committee, we suspected that the songs falling into the latter categories (connections to a BIPOC individual or community, language other than English, and/or contemporary worship music), which together constituted 49% of our music, would be most familiar or accessible to our BIPOC constituents. Conversely, they would be unfamiliar or challenging for many of our white constituents—although I was grateful to receive lots of positive feedback on my musical leadership from them!

The Stories

Based on several of my conversations at the gathering, our assumptions were correct. Here is what I recall in a series of vignettes:

- On the first night of the gathering, we begin worship with a set of three songs appearing on recent CCLI Top 100 lists: Crowder’s “Come as You Are,” Bethel’s “Goodness of God,” and Sinach’s “Way Maker.” A friend with an evangelical background speaks to me afterward about how she was expecting to hear hymns with four-part harmonies and strong ties to Anabaptist history. The contemporary songs raised complex feelings for her because some of them originate in communities with beliefs that do not align with her own theological convictions. At the same time, she appreciates how they diversify our repertoire at this gathering in ways that reflect our increasingly intercultural church. Later, I’m driving with someone whose family has been connected to a predominantly white Mennonite church for multiple generations. She tells me that she was shocked by the sound of this music when she entered the room, although she likewise expresses appreciation for how it challenges a musical norm.

- On the second day of the gathering, I am sharing a meal with a Hmong woman who expresses appreciation for my musical leadership and the variety of songs at this event. Later, I am chatting with a former classmate who was raised in evangelical circles, and he describes how he felt brave enough to raise his hands while we were singing “Way Maker” because there was an Asian woman behind him whose hands were already in the air. As he describes his interaction with her, it sounds like the woman who shared breakfast with me.

- I am returning to my accommodations with a carload of young adults on the second night of the gathering. One of them is pastoring a predominantly white Mennonite congregation. He explains how, when it comes to his own spiritual life, songs with four-part harmonies are more “valuable” than modern worship songs (e.g., “Oceans,” “My Lighthouse,” etc.). At the same time, he acknowledges that songs in the latter category can be very meaningful for other people, even if he doesn’t experience them in that way.

- On the third day of the gathering, a woman with a last name that links her to the Euroamerican Mennonite demographic confesses that, even though it is important to sing the songs of diverse communities and cultures, she hates “Way Maker.” Some of the lyrics feel impossible to sing because they construct an image of God exercising control over us, which can reinforce oppressive church structures that perpetuate harm against women and other marginalized folks. Is it her comment or the fact that I didn’t sleep enough last night that sends me into a wooded area for the last ten minutes of our lunch break to take some deep breaths and blink away tears before returning to the gymnasium to lead another song?

- Later on that day, I ask a few young adults if they can describe the kind of music that they sing in their congregations. One of them is part of a Mennonite church in Vancouver’s Chinatown. He speaks of “contemporary” music rather than songs from a hymnal. There are also two Congolese men who describe their congregation’s music as a progression from energetic “praise” music to slower songs of “adoration.” They cite Elevation’s “Praise” and Bethel’s “Goodness of God” as examples of songs falling into each of the two categories.

In Summary…

Although the “worship wars” of the 1990s and 2000s have ostensibly concluded (Ruth 2017, 4–5), these anecdotal conversations suggest that contemporary worship music still appears to foster a musical division between predominantly white and predominantly BIPOC congregations within Mennonite Church Canada. Perhaps this is true for other denominations as well. (Note: I am generalizing here. For instance, there are plenty of predominantly white congregations that sing contemporary worship music—I was raised in one of them!) If so, how should it shape our approach to curating and leading music at denominational events each spring or summer? Without providing a clear-cut answer by any means, I offer several points of reflection on this question based on what I experienced in Kitchener earlier this summer:

- As a committee, we knew that the majority of the people who would be joining us in Kitchener and singing the songs on our list would be white retirees with a preference for four-part harmonies, but the majority of our repertoire was notated in unison. This discrepancy was not an oversight; it was an intentional effort to decentre a dominant musical expression and show that our denomination affirms other ways of singing and worshipping together—especially those ways of worship that are beloved by people who do not fall within the ethnic majority.

- If contemporary worship music is the preferred genre of many predominantly BIPOC congregations, we must be wary of contemporary worship music functioning as tokenism when it is sung in predominantly white spaces. In other words, inserting a single Elevation or Bethel song into an order of worship that is still structurally white (e.g., a series of discrete readings, songs, and prayers that can appear on a piece of paper in linear order like a to-do list) would not be enough to affirm contemporary worship music as a valid expression of faith within our denomination. Our committee therefore made the structural change of using a worship “set,” featuring several contemporary worship songs in a row with a smooth musical progression and extemporaneous words or prayer between them (Lim and Ruth 2017, 32).

- It is an unfortunate reality that much of the theological critique that people level against contemporary worship music can also be directed at “traditional” hymnody. While a line like “Lay down your shame” combined with “Oh, sinner, come kneel” in Crowder’s “Come as You Are” could reinforce a false sense of shame or wrongdoing for survivors of abuse, we might also critique the highly submissive plea to “melt me, mold me, fill me, use me” in a four-part song like “Spirit of the Living God,” which appears in most denominational hymnals of the last century. Both songs carry the potential to heal or harm, and we must exercise care when leading either of them.

Finally, on a concluding note, it is impossible to meet the needs of every individual or community at a single event, which is why I would not necessarily adhere to the same statistical framework if I were choosing songs for Mennonite Church Canada’s next gathering in 2028. We chose songs that we hoped would bring our intercultural commitment to life by privileging the voices and/or experiences of BIPOC communities. If a future gathering engaged with the theme of undoing harm against women or queer folks, for instance, I imagine that I would take a very different approach to curating songs. While I don’t know if such an opportunity will come to me again, nor do I feel confident that I nailed this one, I pray that Mennonite Church Canada’s “Billboard Top 40” list will continue to evolve in ways that bring us into richer relationship with God and each other.

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration and a Master of Theological Studies. She obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada. Currently, she is a PhD student in the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, ON. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She also co-directs Ontario Mennonite Music Camp and chairs the team of volunteers who maintain Together in Worship, a curated collection of free worship resources from Anabaptist sources.

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration and a Master of Theological Studies. She obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada. Currently, she is a PhD student in the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, ON. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She also co-directs Ontario Mennonite Music Camp and chairs the team of volunteers who maintain Together in Worship, a curated collection of free worship resources from Anabaptist sources.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience. I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us.

I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us. Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable.

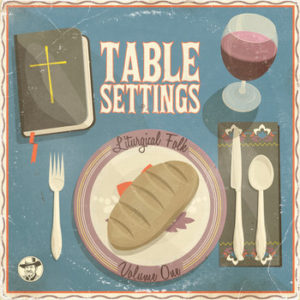

Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable. Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “

Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “