Blogger David Bjorlin is a worship pastor at Resurrection Covenant Church (Chicago), a lecturer in worship at North Park Theological Seminary (Chicago), and a published hymnwriter.

In my previous blog post, I argued that, for most people in the United States, consumerism is one of the most prevalent forces that drives our national economy and heavily influences the seemingly “free” choices we make as individuals and communities. Indeed, because it is so immersive—because it is the very waters we swim in—it is difficult to step back and see how vast its influence actually is on every facet of our lives. Naturally, congregational song is not immune to these consumer forces. In the last post, I explored the CCLI Top 100 list and how the fact that two companies distribute the vast majority of the songs limits the ethnic and theological diversity of song for those churches that use the list as their main resource for selecting worship songs. In this post, I want to explore the concept of planned obsolescence and how it might influence the life cycle of congregational song and how congregations use these praise songs.

What Is Planned Obsolescence?

Planned obsolescence is a strategy where producers purposefully create products (planned) that will become obsolete (obsolescence) after a certain period of time, requiring the consumer to replace the product. While this concept may seem abstract, most of us probably can relate to something like the following story: the latest edition of the iPhone (or fill in your favorite phone brand of choice) comes out. While the price is a little bit of a stretch, you decide to spring for it. For the first few months, you’re thrilled with all the new features, not to mention the sleek design and shiny exterior. But about a year in, the new design comes out. Ten months later, another design comes out. Soon, when you try to purchase accessories for the phone (e.g., headphones), you have a hard time finding new products that will work with your “old” phone without a series of adapters. The year after, when you go to update your phone, you’re told that your version of the iPhone doesn’t support the new software. So, you bite the bullet and begin looking for a new iPhone. This is planned obsolescence.

Perhaps the downsides to planned obsolescence are obvious, but I think they are worth enumerating for the purpose of our discussion. First, the strategy can negatively influence the quality of the product sold. Why bother with the best materials or craftsmanship when the product will only have a shelf life of several years? Second, planned obsolescence can negatively influence the way we consume products. Rather than caring for a product as if we were going to hand it down to the next generation, we treat the product as disposable because it was made to be disposed of after a certain amount of time. The care and repair of goods is no longer seen as a valuable practice or trade, for why would anyone learn to darn socks or repair shoes when you can just toss them and buy cheap new ones? Finally, all of this leads to environmental degradation as obsolete products pile up first in closets and junk drawers and then in landfills around the world.

Planned Obsolescence and Congregational Song

So, how does the economic strategy of planned obsolescence impact congregational song? I would argue in many of the same ways it influences our consumption of goods more generally. First, it changes the way we consume songs. Like disposable goods, congregational song becomes one more product to consume and discard. Again, perhaps many can relate to a process I’ve experienced dozens of times as a worship leader: A new praise and worship song comes to my attention that I think would be perfect for my congregation. So, I decide to introduce it to my congregation. The first week people seem to really enjoy it, struggling with the verses a bit but joining in wholeheartedly on the chorus. The next week I plan to do it again to help reinforce it, and I can tell something has clicked between this song and the congregation. The singing is strong, the flow is natural, and many people comment about how much they enjoyed the song after the service. By the third time we sing it, people unabashedly love it and begin requesting to hear more of it, which is only reinforced when the local Christian radio station begins playing it regularly too. Over the next year or two, I use it about twice a month, and the congregation almost always responds positively.

But there comes a certain point a year or two down the road where I notice a change. People are still singing, but less enthusiastically. I catch the first moody teenager rolling her eyes when the opening riff starts, and perhaps overhear a snide comment after the service: “That song needs to be put out of its misery.” Just a few months later, the song has officially become persona non grata (cantica non grata?), with people on the worship team loudly protesting about how sick they are of playing it. Luckily, there’s a new song that just came out that seems perfect for the congregation… and the consumptive cycle continues.

I am not the only one to note this trend in praise and worship or its acceleration in the last decade. In his work on the history of contemporary praise, worship leader and songwriter Greg Scheer notes,

Whereas songs from previous eras—“Seek Ye First,” “As the Deer”—remained in the CCLI’s Top 20 songs for decades, new songs tended to rise and fall within a few years. These binge and purge cycles are typical of music that is marketed to the point of saturation and then dropped for the next shiny thing.*

While I might not characterize it as “the next shiny thing,” it seems clear that the way we consume songs continues to shorten the life cycle of the average praise and worship song. And I can’t help but believe that this at least unconsciously changes the way writers of praise and worship songs approach their craft. If the song cycle of a song is only a couple years at best, why spend the extra time on the smaller details of song structure or rhyme scheme, or think through questions of gender-inclusive language for humanity and God (for example)? Why try to write a song that could stand the test of time across generations when the system is built to consume and discard what you have made? Again, I don’t think songwriters say to themselves, “I’m going to create something shoddy!”, but I believe that these economic forces often work on us whether we are aware of them or not. Being conscious of these forces is the way we can begin combatting them.

What Can We Do?

So, what are some possible strategies for worship leaders to help avoid planned obsolescence in congregational song? First, and most obviously, worship leaders can choose songs from across generations. We as the church are heirs to a rich storehouse of musical treasures from every era of the faith, and we honor that living tradition when we sing the songs that have been handed down to us—whether that is plainsong from the 1180s or a Scripture song from the 1980s. In rejecting the idea that new is better in congregational song, we not only honor our tradition, but help check some of our consumptive habits. Second, we can choose not to overuse new congregational songs. Yes, we should teach new songs well, which will include repetition over several months, but we should also resist the urge to completely consume the song. Like a gift of fine whiskey, we can portion the song out over time rather than binge on it so that it can be mindfully savored rather than thoughtlessly consumed. Finally, we can seek out songs that are thoughtfully and skillfully crafted within the paradigms of their particular genre, so they stand a chance of lasting beyond the life cycle of a Top 40 song. In these ways, we can play a small part in taking a countercultural stance against consumerism in the song of the church, and perhaps this will lead us to examine other ways we can choose conservation over consumption for the sake of the Gospel and the good of our world.

*Quote is from: Greg Scheer, “Contemporary Praise and Worship,” in Hymns and Hymnody: Historical and Theological Introductions, vol. 3 (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2019), 287.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience. I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us.

I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us. Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable.

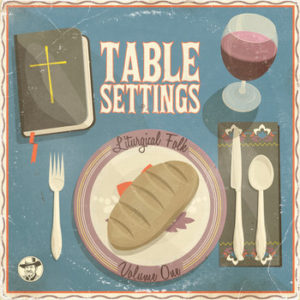

Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable. Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “

Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “