Author – Adam Perez is a doctoral student in liturgical studies at Duke Divinity School.

In this blog post, I want to offer some simplified responses to the question, “Why do Christians sing in worship?” My response is not simply my own, but a compilation and summary of a wide variety of church music and worship textbooks, ethnomusicology books, popular worship books, and other commentary I’ve encountered in the adventure of preparing for my doctoral exams. I offer this not to recommend any one of these rationales, but so that we can see a fuller picture of why faithful Christians across the spectrum of denominational and ecclesial tradition have found it fitting to sing as an act of worship. (N.B. I’ve likely left something out, so fill in the gaps by commenting below!)

Scripture’s Model and Command

Throughout Christian scripture, music-making is regular. Unfortunately we don’t know very much (if anything) about the actual musical sounds or music-making practices. However, some scriptural examples seem to expressly command the practice of music making in worship. One important reference is Paul’s recommendations to the Christians in Colossae (Col. 3:16, also Eph. 5:19) to “sing Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual songs to God.” The presumed context for this command is corporate Christian worship (and possibly simply as a way of being in community in general). Likewise in the Psalms, the Psalmist commends the reader/singer to “come into God’s presence with singing” (Ps 100), to “sing to the Lord a new song” (Ps. 98), and many more.

Beyond commands, scripture models song and singing. Job suggests that the stars sing, Psalm 150 suggests that all creation praises in song, and in the OT prophets and in the NT scriptural canticles, song is modelled as an appropriate action for Christians. In particular, some songs are presented as fitting responses to God for God’s actions in salvation history: the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis as well as the heavenly chorus’ song in Revelation 4, 5, 7. Paul also potentially embeds song lyric in the ‘kenotic hymn’ in the letter to the Philippians chapter 2.

Especially in the scriptural canticles and in the Psalms we see that song is an appropriate action for responding to God’s mighty acts of salvation—the logic that is preserved in the so-called “Great Thanksgiving Prayer.” Because God has acted for the salvation of God’s people, God’s people sing praise in response. Many commentators from various backgrounds assume that when God is praised in the OT, some musical activity is presumed (i.e. the traditions of interpreting “the seven Hebrew words for praise”).

These examples point to one last, related point: song is part of telling God’s story to others; in song, God’s actions are preserved, remembered, and communicated. In this way, singing to others can be part of sharing or witnessing to the Gospel.

The Human-ity of Music

A second set of rationale for using music into Christian worship is two-fold: music is deeply human and it has great potential for forming social/ecclesial relations. Some authors go further and suggest that singing is part of becoming more fully human. They suggest that given that such a marginal portion of the population is, scientifically-speaking, ‘tone deaf,’ it is safe to assume that the capacity to produce differentiated pitches in song is part of being human. We might call this simply an anthropology that centers singing.

But it is not simply limited to the idea that individuals are able to sing, but that their singing nature is able to help them participate in a larger web of social relations. Take, for example, the fact that singing has an especially important role in the history of social movements and reforms, from the Reformation to Civil Rights to Hong Kong. Song and singing capacitate humans toward action outside of themselves (both for good and for potentially for ill).

Music also has the capacity to both create and communicate group identity. Because music is a part of culture, it can embody the particularity of a local community and extend that community’s identity beyond itself. Music and song have an important role in the cultural preservation of diasporas as well as in forming new communities. For this reason, it is also essential in the multicultural worship conversation that diverse musical practices are led by persons who are able to ‘authentically’ represent the communities from where those songs come. In this way, cultural communication and authenticity are intimately intertwined with music-making in worship.

Musical style in particular has been contested because it carries with it the capacity to structure social relations in very specific ways and thus is a site of ethical formation. One great example of this is in Monique Ingalls book Singing the Congregation (Oxford, 2018). She describes how worship at the Passion and Urbana conferences is the prime way in which the community is formed as an ‘eschatological’ body. The musical worship practices situate social relations both now and as a reflection of future heavenly social relations.

Lastly, music is seen as uniquely able to evoke or embody emotional responses. As such—and insofar as this is a desirable goal of Christian worship—music is capable of creating or generating emotional responses in persons and groups. For the sake of the “warm ups” of Finney-esque revivalism, music is seen to ‘plow the [emotional] soil’ so that the seed of the Gospel can be planted and take root. This same is true, though in a different musical register, in church contexts where so-called “art music” is presented for detached aesthetic contemplation. The logic is this: because people are naturally vulnerable to emotional states produced by music, music might make them receptive to a certain kind of Gospel message.

One additional note here of historical importance: the creaturely or emotional effects of music have been highly contested. In the Protestant Reformation, for example, there was deep suspicion from Zwingli and Calvin (drawing on Augustine) on music’s capacity to move the emotions. It was also seen as being able to affect the internal humors of the body and have effects on the health of the hearer. In metaphysics, it was understood that earthly music could sync up with the cosmic ‘harmony of the spheres’ (Plato, Boethius, and neo-Platonists around the time of the Reformation) through formal mathematical relations. Some Reformation debates on the topic of music can be summarized as to the question of the extent to which music was tainted by the effects of sin (especially pre- or post-lapsarian). To render it simplistically: is music inherently good or bad? The answer has some determination on the utility of music for Christian worship today. Luther, for example, saw it as inherently good and therefore trusted that it was good for humans to participate in it for Christian worship. The issue lingers on today when, for example. mid-20th century evangelicals resisted Rock-n-Roll music on the basis that the rhythm was evil or could conjure up undesirable, ecstatic, emotional frenzies among ‘the youth.’ This fear of particular musical styles was rooted in a not-so-veiled musicalized racism–only their music is tainted by sin and evil, ours is pure.

For Doing Worship

The final rationale for the use of music is in music’s capacity to help facilitate the doing of worship. A number of authors advance this basic position, though there is some divergence as to what exactly the essential actions or dispositions of Christian worship are or should be.

On the most basic level, historically-speaking, singing has been useful for carrying the voice through worship spaces and for facilitating group proclamation (eg. chant). Admittedly, electronic amplification now serves to carry the voice in many spaces regardless of one’s ecclesial tradition.

Traditionally, music also has enjoyed a close relationship with, and is especially fitting for the activity of praise. Whether that praise is enacted by the entirety of the gathered worship assembly, or on their behalf by clergy. Again, Christian worship’s model here is the scriptural witness in songs and canticles.

Evangelical church music texts especially highlight the capacity for music to convey a text while rendering music subservient to the text. Music is seen to function primarily in its instrumental capacity to support the communication of a text and aid in the text’s comprehension. Specifically the musical poetic form of the hymn is useful for unfolding doctrine in poetic form as well as telling the story of the gospel in successive, storied stanzas. The church music literature especially likes the hymn form for its capacity to produce inter-textuality as a kind of exegetical tool—again, revealing the emphasis on communicating texts.

On the other end of the spectrum, some theologians suggest that music (especially non-texted music) can disclose something about God in a way that goes beyond a reliance on words. This “non-discursive disclosure” is a counterpoint to the potential heresy that God and God’s character can be totally understood through language alone. Pointing to the person of Jesus Christ as “The Word [who] became flesh” is an important underpinning for this idea.

Music is also an aid to prayer. The phrase “he who sings prays twice” has been attributed to Augustine and is a commonly-invoked rationale (though undeveloped). I’m compelled to note here that the quote from which this adage is drawn might more appropriately be rendered as ‘he who sings well prays twice,’ but that is merely a quibble. Music helps worshippers attend to the Spirit and to the text in such a way that it can aid congregants in quiet contemplation on the one hand, or ecstatic experience on the other. In both cases, music making provides the frame for holistic attention to God. Of course, many songs themselves are prayers to God and thus they function dually in that way.

Lastly, I turn to contemporary praise and worship. While contemporary praise and worship is far from a monolithic tradition, there are some common themes that are shared. The most critical of these is that music and song itself is the essential action when Christian worshippers gather. This goes hand in hand with the way that the mainstreaming of praise and worship has engendered a collapse between the words ‘music’ and ‘worship’ in so many settings. The significance of this is understood by some because it is based on a musico-theological anthropology. Being a Christian means being part of the priesthood of all believers who, like King David and the order of OT Levite priests, minister to the heart of God through musical worship.

In contemporary praise and worship, rather than think about how music can serve some other worship action, music is the essential act that other actions might serve. For charismatics and pentecostals, other ministry time (exercising spiritual gifts) within the service is regularly accompanied by music, if not directly facilitated by it. Experiences of prophecy, healing, deliverance, or other products of the direct encounter with the manifest presence of God are often supported or facilitated by music-making.

Conclusion

While not comprehensive or inclusive of every strand of Christian thinking on the role of music, the above three areas are lenses through which many leaders today see the importance of music and singing in Christian worship. It’s important to note that music and song are not necessary for Christian worship (a variety of Christian traditions attest to this), but that Christians have found lots of thoughtful ways of understanding the role of music in Christian worship: as a commanded and commended by scripture, for deeply human reasons, and for engaging in the acts and encounters of Christian worship.

pain and disappointment along the journey, but the important thing is to acknowledge it and move pass it without allowing the residue of it to determine how we interact with others. Swinton admonished us in his teaching that “…there is no such thing as a dislocated soul.” We will never be effective in our ministries if we are not first honest with ourselves that God loved us first and that love is meant to be shared and displayed in every way at all times to any and every one who comes in our pathway.

pain and disappointment along the journey, but the important thing is to acknowledge it and move pass it without allowing the residue of it to determine how we interact with others. Swinton admonished us in his teaching that “…there is no such thing as a dislocated soul.” We will never be effective in our ministries if we are not first honest with ourselves that God loved us first and that love is meant to be shared and displayed in every way at all times to any and every one who comes in our pathway.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience. I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us.

I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us. Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable.

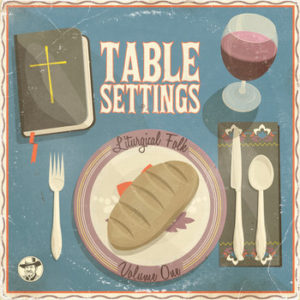

Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable. Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “

Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “