Author – Adam Perez is a doctoral student in liturgical studies at Duke Divinity School.

Worship War

There have been many varied but regular attacks posed by opponents of contemporary praise and worship since its inception in the middle of the 20th century. These attacks have been intense enough to call it a ‘worship war’–and many people have been wearing their battle fatigues to worship every Sunday for the last 25 years. ‘The lyrics are trite or too shallow, ‘the music too repetitive or boring’–or alternatively, ‘too upbeat’ or driven by rhythm (i.e., too similar to the evils of Rock music)—the list goes on. Is contemporary praise and worship a threat to the right worship of the Christian church and its hymnic/theological orthodoxy? Most recently, the critique has revolved not around musical style per se but around congregational participation. Do the speaker stacks and ‘wall of sound’ stun the congregation into silence? Do the performance practices of contemporary praise and worship hinder congregational participation rather than enliven it? Has this always been the case for contemporary praise and worship?

Now, I don’t consider myself an outright advocate of praise and worship, but I do consider my task to be that of dispelling myths and misunderstandings. In this post I want to suggest that, historically, contemporary praise and worship has had the opposite take on its relationship to the issue of congregational participation.

Dispelling Myths and Misunderstandings

The old guard of praise and worship leaders suggest that praise and worship music allows for, creates the space for, even the most unmusical of persons to be involved in musical worship, both singing and playing instruments. Whereas the text-heavy and musically-challenging hymns of old were seen as not-all-that-singable to many untrained musicians, the new, simpler song forms of praise and worship were easily taught and learned. No longer would congregational song be reserved for the specialists (whether a formal choir or the trained singer) as had developed in some circles, but it would be given back to the congregation.

No longer would congregational song be reserved for the specialists

To say that this was simply a change in musical style or in worship practice would be to understate the shift. It wasn’t a shift just in worship practice, but in the relationship between music, persons, and worship. Out of the praise and worship movement came a very important theological anthropology which holds that the core identity of Christians, writ large, is as ‘worshippers’—a trope still very common in many evangelical, charismatic, and pentecostal circles today. This theology was developed in part through a reading of scripture that linked Old Testament worship closely with music-making and was often combined with a strong eschatological vision of worship derived from the book of Revelation. To participate in the heavenly worship, one must sing and make music to the Lord. Singing wasn’t simply the act sine qua non of worship, but singing was part of becoming a right worshipper (cf. John 4:24 “God is seeking worshippers…”), and becoming a right worshipper was an essential to Christian faith and practice as a person. You can see why participation is such a critical issue for praise and worshippers–if singing and music-making were being withheld from the congregation by way of increasing musical difficulty and professionalism, a core component of Christian identity was also being withheld.

This two-fold shift toward making music more accessible and the musicalizing right Christian worship has had an indelible mark on Protestant worship across North America.

Reforms

Often without understanding the basic impulse of praise and worship, one of the primary responses to it has been, “What congregations need [to preserve certain kinds of hymnody] is better music education, not simpler music!” This response, you might recognize, is one that has spurred on educational reforms time and again in the history of church music. Inevitably, reforms of church music and practice have their upsides and their downsides regarding the question of participation. In many instances, especially in the American cultural context, various traditions have generated a subgroup of (semi-celebrity) leaders and performers to whom Americans have allowed to make music on their behalf: the choir’s cantata, the praise band’s set list, the vocalist’s sung testimony, the organist’s Fantasy on [fill in the blank]–not to mention pseudo-liturgical moments like “Special Music,” “Choral Offering,” or “Organ Preludes,” but I digress…

Maybe it’s a cultural thing, maybe it’s a musical thing, or maybe it’s a deeply human thing, but we love to hear expert leaders and performers regardless of our musical or liturgical traditions. And there’s probably nothing wrong with that.

Praise and Worship

But to return to the issue of praise and worship, it seems that the question of participation has begun to rear its head again in the 21st century as the production value of highly visible churches and events has come into question. Though praise and worship initially provided a strong response to this issue, the dissemination and development of it as a tradition has caused transformation in some arenas. We can only speculate the reasons for this, and they are surely many. Some long-time insiders suggest the song composition style is too complex, the influence of recording stars too great, the broader influence of the popular music industry, a disconnect between leaders and congregation, broadening of the teaching on the theology of praise and worship—the list goes on. So to say, yes, this tradition of music and worship may need to re-affirm its commitment to congregational participation—and it is not alone in that need.

Praise and worship is, in its heart of hearts, about and for congregational participation.

Praise and worship is, in its heart of hearts, about and for congregational participation. Though in some very visible manifestations the congregation’s participation seems to have become somewhat tempered or muted, this is not the case for all times and all places. Unfortunately, contemporary praise and worship suffers no more from the cult of celebrity in music and leadership than do many other Protestant churches, mainline or evangelical, conservative or liberal. Likewise, there is no clear correlation between a church’s musical style and the degree of participation in congregational singing, so let’s not pin the issue of participation solely on musical style alone.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience.

One Friday in late July my wife Melissa and I, along with our three young kids, got in the minivan and, as we do every Friday summer morning, headed to the coffee shop. The coffee shop is the epicenter of our neighborhood life. Without compromising the aesthetic of craft coffee culture, the owner, who also has young kids, built his coffee shop with the whole neighborhood in mind, not only hipster Millennials. He did not necessarily design it to be family-friendly; he just built a very good and pleasant place to gather. Sure enough, people of all ages flock there. For a couple hours that Friday morning we engaged naturally in conversation after conversation with neighbors coming and going, babies being passed around, and kids circling us playfully. It is always a truly unmanufactured intergenerational experience. I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us.

I am part of a liturgical church. Liturgy simply means “service of the people.” Paul uses it in Romans 12 to describe the spiritual “service” of offering our bodies as living sacrifices to God. Liturgical practices offer tangible means by which the generations are united in worship. One of my favorite moments of our liturgy is when my children run up to the communion rail to join me in receiving the body and blood of Christ. One Sunday my son knelt down, extended his hands to receive, and said, “Look dad, I’m making a manger.” The old woman to my left started chuckling, and I was inspired by the incarnation illustration my son had just unknowingly given us. Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable.

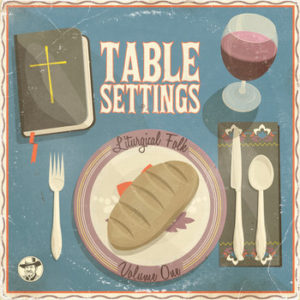

Life is a bell curve of simplicity and complexity. The most unifying songs and rhythms noticeably engage the youngest and oldest among us. If we aim for the people in the middle, those whose lives are most cluttered and noisy, they may connect with the music, but it will be hard for everyone else to participate. Familiarity is the way to go with liturgical music. Familiar doesn’t mean that we need to dumb it down; it means we’re bringing it down to earth, making the music more accessible and the work of the people more doable. Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “

Our music, which we call Liturgical Folk, is a truly intergenerational project. You can read all about it in the Dallas Morning News article, “