Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration. She recently obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada, and she is currently completing a Master of Theological Studies. Mykayla has presented research at conferences in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She works as a worship coordinator for a Mennonite congregation in rural Ontario.

When we sing in unison, we embody unity in Christ. Don’t we?

It was only a few years ago that I first encountered this interpretation of singing with other Christians. I soon realized that it is anything but novel; on the contrary, “commentators from the fourth century onward mention unison singing as expressing symphonia (sounding together, i.e., acclamatory agreement)” (Flynn 2006, 772). The logic is simple: To sing the same thing at the same time, our voices must move in the same melodic direction. It is impossible to sing in unison without unifying our voices, or at least attempting to do so, which equips us for unified action in other areas of life.

That wasn’t my understanding, though. I once made the opposite claim in an assignment for one of my courses. I contended that Christians embody unity by singing in four-part harmonies. Upon reading my work, my professor alerted me to what seemed to be a consensus among medieval Christians: At best, singing in unison unifies us; at the very least, singing in unison serves as a figurative reminder of the concord that should characterize our communities.

How did I develop such a different idea? Where is the logic in my argument?

When I suggest that unity results from singing in four-part harmonies, I am applying the ecumenical concept of “unity-in-diversity” to congregational song (Wendlinder 2018, 390). Rather than prescribing uniformity across all Christian groups, some ecumenists root their vision of the Church in Paul’s description of the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12:14–20:

Indeed, the body does not consist of one member but of many. If the foot would say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” that would not make it any less a part of the body. And if the ear would say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” that would not make it any less a part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole body were hearing, where would the sense of smell be? But as it is, God arranged the members in the body, each one of them, as he chose. If all were a single member, where would the body be? As it is, there are many members yet one body.

While maintaining our diverse beliefs, abilities, or commitments, everyone claims Christ, the head of the Church, as the source of their faith. We represent this inter-ecclesial vision in our congregations when we sing different parts of the same song at once. Diverse musical assignments arise from the same source and contribute to the same goal. Furthermore, by singing different harmonies, a congregation accomplishes more than an individual might achieve alone. In real-time, an individual cannot sing more than one musical line. When it comes to live, sung harmonies, individuals must join their voices together to move in the same harmonic rather than melodic direction. Just like singing in unison, it is impossible to sing in four parts without unifying our voices. The difference lies in working together to build the same chord rather than land on the same note.

I am defending a mode of congregational song to which some Mennonites hold dear. Although I do not descend from sixteenth-century Anabaptists, whether Swiss-German or “Russian” (Dutch and North German), I spend a great deal of time with other Euroamericans who do lay claim to that heritage. For a variety of reasons, most of them untenable, Mennonites in these circles seek to “maintain what they understand to be a Mennonite tradition of a cappella, four-part hymn singing” (McCabe Juhnke 2018, 45). Community ranks high on our list of priorities, but we express our commitment to one another through the sound of diverse voices coming together to form something more than a single melodic line. It’s a beautiful image. It’s also a deceptive image for several reasons that are becoming increasingly apparent to me:

- Isn’t it ironic that a thoroughly uniform group of Mennonites (at least in an ethnocultural sense) embraces a kind of singing that embodies unity in diversity? The multifaceted image of the Church that forms through our song dissolves as soon as we shift our attention to congregational demographics. (I suspect that I’m not just naming a Mennonite problem here. Does anyone else belong to a homogeneous congregation wrestling with the realities of self-contradiction?)

- On the other hand, some Mennonite congregations are not so uniform. I work for a majority-White congregation affiliated with Mennonite Church Eastern Canada, but many of our members did not grow up in Mennonite communities, nor are they able to trace their family lineage to sixteenth-century Anabaptists. Consequently, these members feel less comfortable singing in four-part harmonies. In fact, on a Sunday morning, I often fear that I am distracting or intimidating some of the melody-bound congregants around me if I choose to sing an alto line. (Once again, I suspect that this range of musical abilities is not unique to Mennonite congregations. Are there any other church musicians who worship alongside untrained singers?)

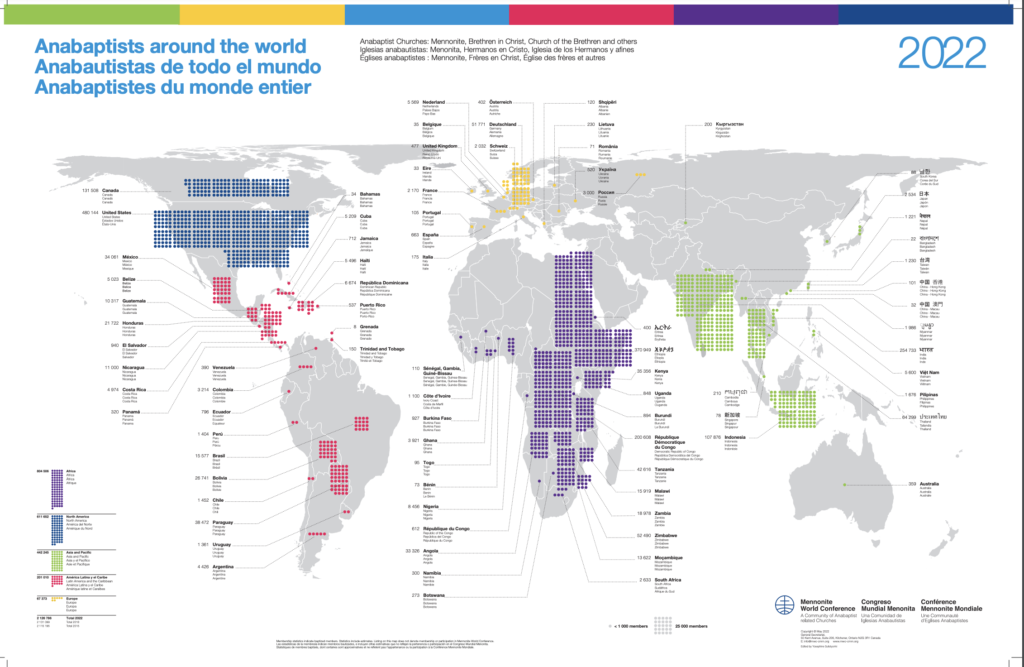

- On a global scale, non-Western Mennonites far outnumber those of European descent. Even in North America, Mennonite congregations that were once ethnoculturally homogeneous are experiencing demographic shifts to reflect global realities (Graber 2022, 193). (I’ll say it one last time: Am I describing a solely Mennonite phenomenon, or are other denominations moving in a similarly diverse direction?) When one adopts this global perspective, it is no longer true to assert that four-part harmonies are ubiquitous among Mennonites (or Christians of any tradition, for that matter). On the contrary, for instance, Katie Graber conducted a project that enabled her to visit a wide range of Mennonite Church USA congregations and observe their diverse musical forms: “I heard a cappella singing, and singing accompanied with piano, keyboard, guitar, drums, and recordings. I heard songs influenced by traditions from around the world, and European and North American hymns translated into many languages.”

Several instructive comments arise from this discussion. On one hand, if congregations in North America are becoming more diverse, it is not so ironic to sing in four-part harmonies after all. When our ecclesial bodies are visibly diverse, consisting of various ethnocultural “parts,” four-part singing symbolically affirms those differences and asserts that unity can still emerge from them.

However, just as it takes considerable effort to bring four vocal lines into harmonic union, we should not assume that congregational unity comes without work. In all areas of congregational life, including the act of singing together, we must exercise hospitality and thoughtful discernment. Singing in four-part harmonies might exclude some individuals who struggle to sing anything other than a melody line. If that is the case, singing in unison might (ironically) serve as a better way to embody unity amidst people of diverse musical abilities. Some of this discernment unfolds at an individual level. When I am singing European hymnody alongside someone less confident in their abilities, I might sing the melody for two or three verses before attempting any harmonies that might distract them. On the other hand, I might be standing beside someone trying to sing the alto line with some difficulties. As a musical leader in my congregation, hospitality compels me to abandon the melody line and support them. When I am selecting music for a congregation representing various musical backgrounds, I might avoid European hymnody altogether, instead choosing contemporary songs that favor a melodic line while still accommodating extemporaneous harmonies. As a keyboardist, when I am accompanying a congregation, I might make careful decisions in advance about whether I should play a song as it is written (to encourage four-part harmonies) or deliberately alter those harmonies so that congregants must sing in unison.

Conclusion

When we sing, we embody unity in Christ. That statement might be true for a congregation that sings in unison. It might also be true for a congregation that sings in four-part harmonies. In truth, it depends less on how a congregation sings and more on how a congregation intentionally includes everyone in the act of singing, which may vary from one song or service to the next. After all, congregational song consists of all kinds of sounds. Sometimes it sounds rich with four or more textures, while at other times, it sounds strikingly smooth. At all times, though, it should consist of all voices or risk evoking little more than an illusion of the unity to which Christ calls us.