Author – Brian Hehn is the director of The Center for Congregational Song.

Denominationally Promiscuous

Although not verified through any written text, it is common for hymnologists and church musicians to quote the 20th century hymnological giant Eric Routley as saying that church musicians are “denominationally promiscuous.” I must confess that I fall into that category. Raised in South Georgia, my father was a former Roman Catholic and my mother a former Southern Baptist. So when it was time to raise us in a church family, they found a liturgical compromise by attending a Presbyterian Church (USA) congregation with solid children’s and youth programs. Upon entering college, I found myself attending and eventually serving as a music intern for a Cooperative Baptist church. After four years there, I entered a United Methodist School of Theology and served United Methodist Churches as director of music for over seven years. Finally, my last two posts as associate director of music have been in a suburban Roman Catholic parish followed by a Roman Catholic Cathedral, where I currently serve. I should mention there was a 1-year period in there when I attended an ELCA Lutheran congregation with my family on Sunday mornings when my primary leadership role was for Sunday afternoon Catholic masses. While serving churches as a church musician has always been a part of my professional life, the other part has consisted of serving ecumenical non-profits and doing conferences/workshops for a variety of churches and organizations.

After working for and worshiping with so many different denominations, I have often asked myself questions like, “wouldn’t it be better to work for the denomination I actually resonate most closely with?” and “is it authentic for me to lead worship in a denomination with which I have some clear-cut theological and/or social disagreements?” These are important questions. But, for me, there’s just nowhere to serve that wouldn’t put me in the same position I’ve been at in every church/denomination I’ve served so far. Every denomination and/or tradition gets some things right and gets some things wrong. Every denomination and church has members that are closer to sinner and closer to saint at any given time. But what I have found in every context so far is that every denomination is full of clergy who have given their lives to try and lead God’s people, every church has staff who are trying their best to lead worship in spirit and in truth, and every worship service has congregants who are trying their best to find the Holy somewhere in this world and in themselves.

I’m grateful for my ecumenical journey, and I’ve learned a lot about my faith and the church universal by spending time with those who think and worship differently than I do. So here are the top three things I’ve learned from each denomination/church I’ve served so far, and the one thing I wish I could tell them.

Testimony is powerful.

Presbyterians (PCUSA)

What I Learned:

- The tradition of strophic hymns and hymn-tunes from the 17th to the early 20th century is rich and important. A particular example that sticks out the most from my childhood is “God of Grace and God of Glory” set to CWM RHONDDA. It’s glorious.

- The reliance on God because of God’s eternal nature and providence. Our long-time pastor started every service for years by reading Isaiah 40:8, “The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our God will stand forever.” This simple truth about God’s nature is ingrained in me, giving me a perspective that helps see me through times when the church, other people, or I mess up. God is bigger than our mistakes, always.

- The organ’s primary role in worship is to lead the people’s song. I was blessed with two dedicated and talented organists during my time growing up who understood this and put it into practice week in and week out.

What I Wish I Could Tell Them:

- It’s okay to use your body in worship…really…it’s ok. In fact, it’s a good thing. Loosen up a little bit for goodness sake!

Baptists (Cooperative and otherwise)

What I Learned:

- Having a different theological or social stance on issues is okay, and you can deal with those disagreements in a healthy way. The first Sunday I attended my Cooperative Baptist Church involved a congregational meeting where folks were testifying about what they did and didn’t believe about God, the church, and certain social stances…and they all listened and respected each other’s thoughts and finally voted on a decision. They moved on as a cohesive congregation who believed in each other’s sincere desire to follow God’s will.

- Testimony is powerful. The number of testimonies I heard over those four years was amazing, and they held power and spoke truth because they were rooted in that community and their collective faith story. The hymn “I Love to Tell the Story” finally became meaningful to me because of their constant witness and testimonies.

- The Holy Spirit is a real thing that moves in ways that can often be surprising! Trusting that the Spirit is actively working and moving is important and powerful.

What I Wish I Could Tell Them:

- Stop identifying yourselves through denominational structures (American Baptists, Cooperative Baptists, Southern Baptists, etc…). It’s undermining the beautiful congregational system that you all have and is a PR nightmare in the 21st Century.

United Methodists

What I Learned:

- The importance of Chuck. Charles Wesley’s hymn texts are one of the greatest gifts to the church universal in the last 300 years. They are beloved by Methodists, Roman Catholics, Evangelicals, ELCA Lutherans, Baptists, Episcopalians and Presbyterians alike.

- New and/or radical theological stances by a denomination can/does spur a flurry of musical output. The open table in United Methodist Worship has inspired a significant number of composers and authors to create new texts and tunes to sing. Some of these hymns and songs have already been picked up by many other denominations and traditions for frequent use…including those who do not profess an open table officially but are doing so in practice.

- Liturgical flexibility can be empowering. When used well, the willingness to be flexible liturgically can allow for powerful worship moments that address modern issues head on and challenge the way congregants think, pray, and act. The United Methodists I’ve hung around with tend to do a good job of honoring inherited worship patterns, while allowing space and time to explore new ideas.

What I Wish I Could Tell Them:

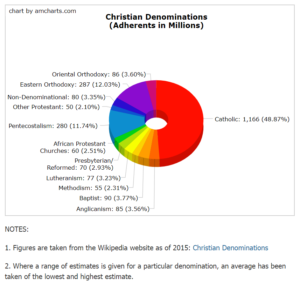

- You’re not as big and important as you think you are. While most (all?) denominations seem to suffer from this in some way, my experience has been that United Methodists are particularly keen on believing that they are one of the “big dogs” in world-wide Christianity. In reality, you are just one of the many pieces of the pie. Important, yes. More or less influential than many other Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox denominations…probably not.

Lutherans (ELCA)

What I Learned:

- There was wisdom in maintaining the order of the Mass during and after the Reformation. To pull vocabulary from the prominent Evangelical worship theologian Robert Webber, there is something “Ancient Modern” about Lutheran Worship because they’ve maintained the Mass structure but have spent the last 500 years contextualizing it to the modern world.

- Taking pride in your denominational identity can be a powerful way to motivate people to study church history and dig into theology. I happened to be attending a Lutheran congregation during the “Reformation 500” year. This celebration was a wonderful exploration not only into what it means to be a Lutheran, but also what it means to be a Christian in the world today.

- The “Lutheran Chorale” is a rich legacy of hymn singing. Like the hymns of Charles Wesley, this tradition of congregational song has become an ecumenical unifier. They are a gift to the church and are used well beyond churches that call themselves Lutheran.

What I Wish I Could Tell Them:

- Stop pretending that Luther sang Bach harmonies…he didn’t. Dig further into your own history of performance practice to inspire yourselves on how innovative you could be in the 21st century by following in the footsteps of all those great Lutheran musicians of the past who innovated and connected your tradition of singing together to the world around them.

People often ask me where I see the future of congregational singing going.

Roman Catholics

What I Learned:

- There is a timelessness to what we do. Singing chant that is over 1000 years old during a Mass whose structure is equally ancient in a building that contains pictures of the saints from the ages reinforces the timelessness of God and of worship.

- A wonderful term for what we (clergy and other worship leaders) do is a “leader of prayer.” If your primary question as a leader is, “how can I lead the people in prayer,” then you’re off to a good pastoral start.

- Even a denomination that prides itself on being the “first church” is often (and usually unintentionally) ecumenical through its congregational song. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, Roman Catholics since Vatican II have been relying on other traditions to help them sing, and they are the better for it.

What I Wish I Could Tell Them:

- You will soon no longer represent the majority of Christians around the world, and you’re already more ecumenical than you realize…just name it, own it, and lead the way into the age of ecumenism.

*This chart taken from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_population_growth

The Future of Congregational Singing

People often ask me where I see the future of congregational singing going. Like the general world-wide trend of Christian denominations and the general population trend of the U.S., I think that we are shifting (or possibly have already shifted) away from a culture of majorities to a culture of pluralities. There won’t be songs that we can identify that the majority of Christians sing. There won’t be genres that the majority of Christians sing. There will be many identifiable trends that are equally interesting, useful, problematic, and complex within the church’s song. And, to me, that means we’re getting that much closer to singing what God sounds like: an intermingling of different pitches, rhythms, and timbres from all times and places that create something beautiful and unexpected.

A future post will deal with the pedagogical implications of working in the church when pluralities are realities.