Guest Contributor – Hannah Cruse is the founder of The Church Musician’s Assistant. She has been working in the church music field for a decade and has a Master of Sacred Music from Perkins School of Theology.

“Why won’t people sit through my postlude? So rude. I spend hours every week practicing, and dangit, I want people to listen!”

Yeah… Frustrating, I know.

So, why won’t people sit through the postlude? What could possibly be the underlying problem? Yes, people want to get to lunch as soon as possible… Yes, not everybody loves music as much as you… But I propose a bigger issue is at stake here: the lack of critical listening skills. You heard me (pun intended)!

Listening

Let me first establish how critical listening is…well, critical. As Christians, we’re called to be good listeners. Proverbs 2 tells us that, “if you receive my words and treasure up my commandments with you, making your ear attentive to wisdom and inclining your heart to understanding…then you will understand righteousness and justice equity, and every good path.” Critical listening opens the door to deeper understanding of how to live according to God.

While undoubtedly essential, understanding only gets us so far. When we insist on always understanding before believing, we possibly cut ourselves off from experiencing the mystical, miraculous God. John 3:11-12 says “Truly, truly, I say to you, we speak of what we know, and bear witness to what we have seen, but you do not receive our testimony. If I have told you earthly things and you do not believe, how can you believe if I tell you heavenly things?” If we only believe what we have seen and experienced for ourselves, we can never know the fullness of God. We must listen for what we do not know. Only through critical listening can we glimpse heaven.

Furthermore, critical listening can save our souls, boldly claims John 1:19-21. “Know this, my beloved brothers: let every person be quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger…Therefore put away all filthiness and rampant wickedness and receive with meekness the implanted word, which is able to save your souls.” How can listening save us exactly? Well, it’s all dependent on what happens after we listen. “But be doers of the word,” says John 1:22, “and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves.” We are called to go out into the world and be disciples of Christ 24/7. Listening is just the first step in our long journey towards Christ.

As musicians, we know all about listening. Most people, though, have no formal occasion to practice listening skills. In fact, popular culture loathes listening. Society would much rather tout self-righteous correctness than show its growing edges to the world. What a shame. How can we expect people to sit through our postludes when they haven’t been taught why or how to listen? If our educational system and our society won’t teach listening skills, then we, the Church, must!

Church Musician’s Role

So what is the church musician’s role in all this? Church musicians are perfectly positioned to teach critical listening skills. There’s nothing like music for arresting the attention. In order to make listening a priority in our music ministries though, we need a game plan with actionable steps. Below are some ideas for transforming your absent-minded congregation into a listening congregation.

Model good listening for your congregation by improving your own critical listening skills.

Always start by praying for the Holy Spirit to speak through your music. We’re pretty useless without the Spirit anyway. In addition to prayer, be open-minded. Be open to friendly, respectful theological arguments with your colleagues and congregants. Instead of responding angrily to opposing viewpoints, just say “Gosh, I hadn’t thought of that before. I would like to pray about this and get back to you so that we can continue this fruitful discussion.” If you aren’t already, begin to have thoughtful conversations at choir or ensemble practice. Genuinely ask for the opinions of your musicians and take those opinions into consideration. And if you ever start to feel aggravated, just remember 1 Corinthians 13:4-8: “Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails.” Prioritize active listening for yourself so that others might be inspired to do the same.

Build trust with your congregation so they will respect your instruction.

Trust is an essential component of any healthy relationship. Would you follow a military general blindly into the night if he couldn’t shoot a gun properly or had no tactical plan? In Paul’s words, “Me genoito (hell no)!” Your congregation, likewise, will not heed what you have to say if you do not exemplify expertise and excellence in all you do. You’re probably thinking, “So all I have to do is get a fancy degree and play well?” Wrong–sorry! There’s another component more important than expertise or excellence: humility. As Philippians 2:5 says, “Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus: who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness.” If you do fantastic work and demonstrate humility, your congregation will likely follow you into the darkness with confidence.

Foster communal music-making during worship so the congregation can practice listening to their neighbors.

Reciting texts together in worship is certainly beneficial, but there’s something extra special about singing together. Singing in public–surrounded by people you talk to at coffee hour every week–is a huge act of bravery. Singing is deeply physical and personal. When we sing in the midst of others, we expose a little piece of our souls. In these moments, we get to practice listening without judgement and encouraging with love. As written in Hebrews 10:24-25, “let us consider how we may spur one another on toward love and good deeds, not giving up meeting together, as some are in the habit of doing, but encouraging one another—and all the more as you see the Day approaching.” When we bare our souls to each other through song, we suddenly see that we are not that different. We all love the Lord. We are all vulnerable. We all want to be better people. Through communal singing, we witness beauty in diversity and strength in unity.

Teach your congregation how to enjoy and listen through the silence.

This is a tough one because we typically despise awkward silence. However, we can teach congregants that silence is not awkward. Lamentations 3:26 instructs, “It is good that one should wait quietly for the salvation of the Lord.” Silence allows space for meditating on the Word, listening to God, praying individually, and noticing the network of believers around you. Try to work with your pastor to find appropriate moments for silence in worship. Experiment with giving each segment of the liturgy due respect and time. Often, we attempt to avoid “wasting time” by overlapping segments of the liturgy. For example, while one reader walks to her seat, another might walk past her to the lectern. Or, while the pastor prepares the communion table, the musician might noodle through some chords. How might worship feel if we waited for the reader to sit down before anybody else stood up? How might it feel if we intently watched the pastor prepare the communion table in silence? What might it be like if we allowed each segment of the liturgy to speak for itself? I wonder if waiting in silence could help us listen better. Sometimes, we need to experience one extreme in order to appreciate the other. As Ecclesiastes 3:7 says, “There’s a time to keep silence, and a time to speak.”

Stimulate your congregation to listen critically by programming edgy music.

What do I mean by edgy music? Any music that challenges the status quo, that makes people feel a little bit uneasy. Definitely read the temperature of your congregation and don’t go overboard on this! However, it’s important to stretch people beyond their comfort zones occasionally. You will probably get a few complaints from members… Don’t be discouraged. If your congregation trusts you, they will generally tolerate–or even enjoy–your little expeditions into the unknown. “What’s the point of stirring things up?” you might ask. Well, when we get too comfortable, we often become set in our ways and closed off to others. We forget to listen. So we have to be reminded to listen–sometimes by music as shocking as a bucket of ice water over the head. When we actively listen to that which is different, we start to understand it, and then perhaps we can grow to love it.

The Original Question

Let’s return to the original question… “Why won’t the congregation sit through my postlude?” Because the Church has not properly taught its followers how or why to listen. People don’t listen to things that don’t matter to them. So before condemning church-goers, perhaps we should examine our own work. Have we educated our congregations about the vitality of sacred music for their spiritual lives? Have we modelled open-minded listening as leaders? Have we encouraged listening to neighbors through communal singing? Have we stimulated critical thinking in our congregations through purposeful silence and boundary-pushing? Education is key to forming congregations that listen well. You have the power as a musician to teach your congregants how to listen with open minds and hearts. Let the transformation start with you.

Guest Contributor – Hannah Cruse

So, like the guitar amp in This Is Spinal Tap, we grow accustomed to a 10, so we try to turn the next service up to 11. Hedonic adaptation tells us that this is a losing game. When every Sunday has to be a mountaintop experience, we have to keep elevating the mountain to give worshipers the same emotional experience. From what I have observed, this tends to lead to an insatiable congregation and a burnt out pastoral staff.

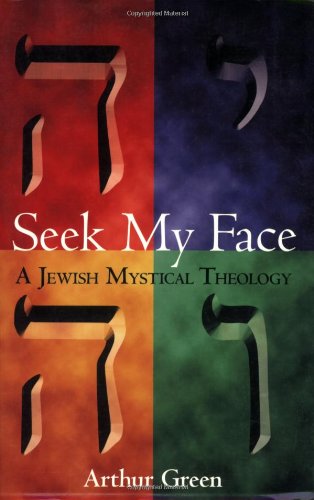

So, like the guitar amp in This Is Spinal Tap, we grow accustomed to a 10, so we try to turn the next service up to 11. Hedonic adaptation tells us that this is a losing game. When every Sunday has to be a mountaintop experience, we have to keep elevating the mountain to give worshipers the same emotional experience. From what I have observed, this tends to lead to an insatiable congregation and a burnt out pastoral staff. Perhaps one possible remedy to this problem of hedonic adaptation in both worship and congregational song is to use other spatial metaphors for worship. What if we are not always moving to the heights of ecstasy but also to the depths of being, not inhaling to climb higher but exhaling to sink deeper into God’s embrace? In Arthur Green’s Seek My Face: A Jewish Mystical Theology, he suggests just such a proposition for a new way of understanding spirituality:

Perhaps one possible remedy to this problem of hedonic adaptation in both worship and congregational song is to use other spatial metaphors for worship. What if we are not always moving to the heights of ecstasy but also to the depths of being, not inhaling to climb higher but exhaling to sink deeper into God’s embrace? In Arthur Green’s Seek My Face: A Jewish Mystical Theology, he suggests just such a proposition for a new way of understanding spirituality: