What a Hymnal Does

I love hymnals for lots of reasons. I love that hymnals, especially denominational hymnals, showcase the breadth of the whole Christian tradition, as well as the depth of my own Mennonite tradition. I love that newer hymnals feature chord symbols in addition to SATB harmonies. Some hymnals include thoughtful essays, readings, and liturgies in addition to an expansive repertory of music, and I love that as well.

Perhaps most of all, I love that hymnals organize songs into categories that make liturgical sense. For instance, when browsing my congregation’s hymnal, Voices Together, a few weeks before Easter Sunday, it is so convenient to refer to the “Jesus’ Resurrection” section and find a wealth of suitable songs. If I need additional suggestions, I might consult the thematic or scriptural indices at the back of the book. Most of the time, though, I find what I need by visiting the section of the hymnal that corresponds with the current liturgical season. Some sections might also correspond with a specific instance of congregational life, like the “Death and Eternal Life” section that includes suitable songs for funerals.

What a Hymnal Doesn’t Do

As much as I love my hymnal, there are limits to what it can offer if I take its organizational structure at face value. For instance, we are in Ordinary Time right now, and I don’t often see “Ordinary Time” when I look at a hymnal’s table of contents. Even when I utilize what does appear in a table of contents, it’s tempting to skip sections like “Death and Eternal Life” when selecting music for a Sunday morning, since I am apt to assume that these songs are exclusively appropriate for funerals. If I’m using Voices Together, I might therefore never encounter a song like Pablo Sosa’s “El cielo canta alegría”!

Although I commend the editors of this hymnal for carefully determining where “El cielo canta alegría” best fits among such a range of categories and themes, I must also acknowledge the relative arbitrariness of their decision. Pablo Sosa did not originally write this song for a funeral, and many of the song’s themes and references are transferable across a variety of settings. It works for a funeral, but it works in other cases as well. That means that I miss some of what a hymnal might bring to my congregation if I hold too fast to its table of contents or narrowly define what a section like “Death and Eternal Life” implies.

What a Hymnal Could Do

Similarly, how often do I assume that the “Jesus’ Resurrection” section of the hymnal is sacrosanct, reserving it for Easter Sunday and ignoring it in all other situations? Keeping with the theme above, I recently attended a funeral that challenged this assumption, since we sang “Lift Your Glad Voices” to conclude the service. It served as a beautiful celebration of eternal life in the wake of a loved one’s death. It works for Easter Sunday, but it evidently works in other cases as well—even a funeral!

When selecting music from a hymnal, we all know that we need not bind ourselves to its table of contents. Still, it’s often convenient for us to take this approach. It reduces time and effort. However, it also reduces our creative impulse and limits our theological imagination. For that reason, I suggest that Ordinary Time is an ideal opportunity to recall that there are songs which warrant our attention in the sections of our hymnals that we are least likely to consult.

Lessons from a Liturgical Calendar

Indeed, for those who follow a complete liturgical calendar, Ordinary Time is the most flexible season of the year. On these Sundays after Pentecost, according to most lectionaries, the biblical storyline is less linear than Jesus’ birth, life, death, and resurrection. It creates more room for experimentation, leading some congregations to explore alternative themes or scriptural texts over several weeks. It might mean studying an entire book of the Bible or engaging with a theme that reflects the experiences or circumstances of your congregation.

Ordinary Time creates more room for musical experimentation as well:

- It might mean learning a new song that doesn’t explicitly correlate with a liturgical season.

- It might mean singing a familiar song at an unfamiliar time.

- It might mean turning to sections of the hymnal that we failed to notice earlier in the year.

It might even mean searching beyond the hymnal for musical ideas. Every hymnal overemphasizes some themes while deemphasizing other important topics. Further, hymnals only contain songs that were written before a certain date. How might the freedom of Ordinary Time inspire us to consult other sources, perhaps introducing us to new composers, musical genres, styles of worship, or theological themes?

The possibilities are far more numerous than we often take time to acknowledge. Like a liturgical calendar or set of lectionary texts, a hymnal is richer than what we often assume, while, at the same time, it is far from comprehensive. We exercise wisdom as church musicians when we intentionally balance respecting, redefining, and removing the boundaries that a hymnal sets for us. If we forget to strike that balance, Ordinary Time serves as our annual reminder.

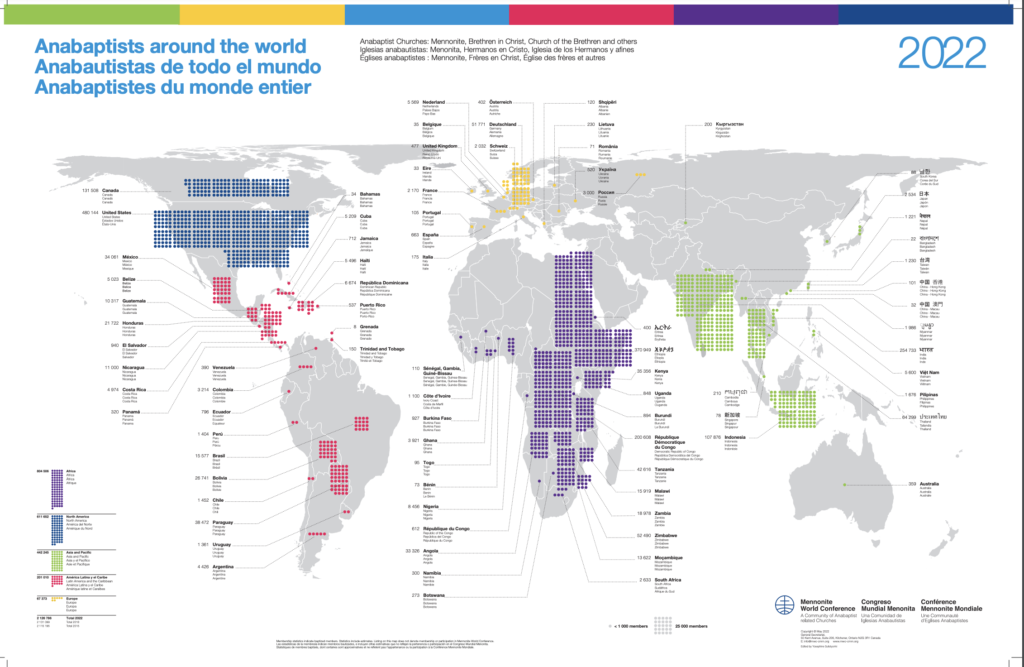

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration. She recently obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada, and she is currently completing a Master of Theological Studies. Mykayla has presented research at conferences in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She works as a worship coordinator for a Mennonite congregation in rural Ontario.

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration. She recently obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada, and she is currently completing a Master of Theological Studies. Mykayla has presented research at conferences in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She works as a worship coordinator for a Mennonite congregation in rural Ontario.

This month, I started working for a Mennonite congregation in rural Ontario. I serve as a “worship coordinator,” meaning that I select music, develop service themes and orders, and equip congregants for various liturgical roles. The congregation selects repertoire from Mennonite Church Canada and Mennonite Church USA’s most recent hymnal, Voices Together (Kauffman 2020). This hymnal made headlines in the world of congregational song for its richly diverse repertoire deriving from a variety of linguistic, stylistic, and cultural sources.

This month, I started working for a Mennonite congregation in rural Ontario. I serve as a “worship coordinator,” meaning that I select music, develop service themes and orders, and equip congregants for various liturgical roles. The congregation selects repertoire from Mennonite Church Canada and Mennonite Church USA’s most recent hymnal, Voices Together (Kauffman 2020). This hymnal made headlines in the world of congregational song for its richly diverse repertoire deriving from a variety of linguistic, stylistic, and cultural sources.