This post, written by Edward Anders Sövik, was originally published in the peer-reviewed journal The Hymn in 1990. As with many topics concerning the church’s song as well as the field of architecture, the advice and wisdom written remains true many years later.

A beginning in the understanding of church architecture is the recognition that the worshiping community is not an audience. Kierkegaard observed that if we wish to think of Christian worship as theater, we ought to remember that the whole assembly is the cast and God is the audience. Worship is common worship, something we do together. As on a stage, there are many parts of a liturgy that are given to particular persons; but we never think that others in the cast of a play are then passive; similarly in the liturgy, nobody in the cast is passive. And the sense that we are doing something together is never so clear as when we sing hymns.

One basic intention of church architecture is to provide a place where people can perceive that their “togetherness” has shape and clarity. A building can accommodate this in two ways: with its configuration of seats and with its acoustics.

SEATING CONFIGURATION

The unity of a family is both established and symbolized by the dining table or the hearth; we speak of “gathering around.” If you ask a group of people, young or old, to sing together in an empty space without an audience, they will almost inevitable gather in a circle. When an orchestra performs, its members wish to hear each other, so they deploy in a half-circle; if there were no audience and no conductor, the shape would more likely approach a full circle. It is equally important to arrange hymn singers so that they can best hear each other because they can thus establish their unity through song. (The recitation of the creed profits equally from an arrangement in which people see each other face to face; it is, after all, to each other that we make the confession.) We sing for each other and not simply to God. It may be useful to consider that as we think of Christians as the “hands of God” when we do God’s work in the world, so we are in a sense God’s ears when we listen to music in worship. When we sing hymns, it is proper that we should hear and be heard.

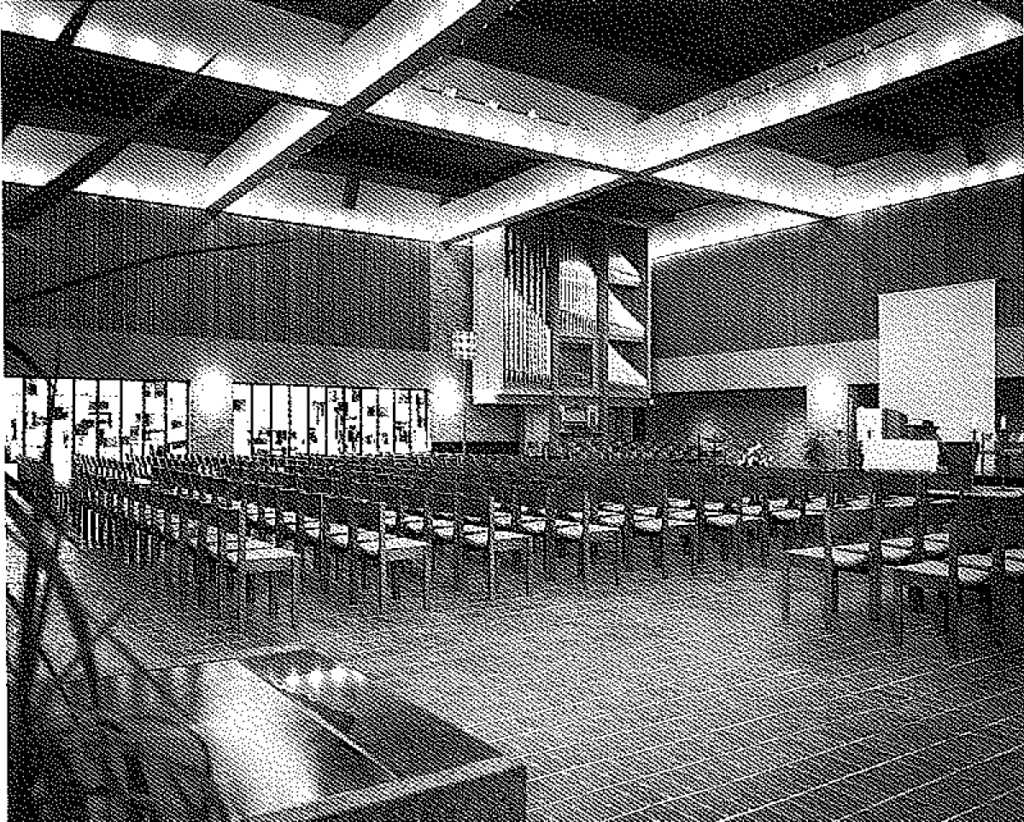

Rectangular rooms of this size need some absorption. People and chair cushions provide some at floor level. More absorption is provided by slotted wood wall boards on two walls.

The appropriate configuration for hymn singers then is not the long, narrow scheme of cinema seating, but something more like a circle or square or wide rectangle, where people are much aware of others in the assembly and have a stronger sense that they are a single body whose parts belong together. Architectural configurations of this sort are appearing regularly in new church buildings. Sometimes the configuration is a full circle, which surely is the strongest affective symbol of the unity of the worshiping assembly. More often, it is a fan or some variation of a fan. The perfect fan shape—especially if the floor is dished—may seem at first consideration to be a very good one, but it is not. The reason is that concentric arcs of seating come to focus on a center point. Though the comparison to a bullring or arena may be exaggerated, it is not inapt; in the arena, architecture “instructs” people that they should pay attention, not to each other, but only to the thing or event at the center. This is not appropriate for hymn singing (nor for some other episodes in participatory worship). A geometry that is not as static as a fan or circle and does not so clearly imply an audience/performer division is preferable. (Cylinders, squares and other shapes of such simple symmetry bring with them acoustic difficulties, though these are not necessarily invincible.) There are several traditions in the history of church buildings that configure the shape of the assembly in a broad rectangle or a square; the New England meeting house, with its pulpit centered on a long side of the rectangle and people arranged orthogonally is probably the best known in this country.

The wood ceiling is a series of convex panels, aiding hymn singing.

ACOUSTICS

The acoustics that are appropriate for hymn singing are sharply different from the acoustics proper for most other places of assembly; they pose for an acoustician and architect a more difficult problem.

A typical concert hall, theater or lecture hall is supplied with a stage, platform or dais, which is the source of the sounds with which the audience and acoustician are concerned. The acoustician tries to be sure that the sounds from this source can reach all parts of the room, that the surfaces are such that there are no direct echoes or flutter, that the quality of sound is not distorted and that the sound is absorbed after a lapse of time (reverberation period) that is long enough to provide a kind of richness, but short enough so that articulation is not blurred.

In this sense, the place for worship is similar to a concert hall because the pulpit, altar-table, lectern, choir and organ may be seen as similarly on stage. These sources of sound are localized. The circumstances are somewhat complicated in a place of worship because the sound is sometimes speech and sometimes music. The reverberation period of a room in which speech has it [sic] clearest articulation will be a good deal less than that of a room where music is to be heard in it [sic] richest colors and tonalities. This disparity usually is met by planning a compromise at some intermediate reverberation period. (More on this subject later.) The question of reverberation time is not a specific issue for hymn singing; if a room is satisfactory for an organ or other musical instruments, the reverberation time will be satisfactory for hymn singing.

Rooms that are designed with a single sound source usually provide hard, reflective surfaces near that source to help project sound out and some soft, absorptive surfaces distributed elsewhere to prevent echoes or flutter or blur. Stage floors, for instance, are never soft, although the aisles and floor in the audience area may be carpeted. Ceilings also will be reflective over a platform, but may be sound-absorptive over an audience. The great difference between most places of assembly and places of worship arises because hymn singing asks that the whole room be seen as a sound source; it is all a stage. Ideally, sound could be generated anywhere and heard everywhere, so that the hymn singers perceive themselves not as soloists but as part of the whole body acting together.

Hymn singing asks for surfaces that reflect sound abroad no matter where the origin is, and is not much interested in absorptive surfaces. It must be remembered, or course, that absorption is unavoidable. Even hard surfaces absorb some sound, and as soon as a room is full of people, there is a great deal of absorption because the equivalent adsorptions of the average person is something more than three square feet of open window.

DESIGN DECISIONS

Considering these things, architects can make some commonsense design decisions that can give rooms the appropriate acoustics for hymn singing. Because the floor surface, occupied by people, is absorptive, the ceiling surface should not be. Furthermore, the ceiling preferably should not be flat, because if it is, all singers’ voices will come back to them directly on the first rebound of sound, and they will not hear other people as well as they ought. Ceilings may be coffered or sloped or undulating or otherwise sound-diffusing. There is a logic also in a hard floor even in aisles simple because, if there is absorption such as carpet added to the floor level absorption provided by people, there is likely to be too much absorption. Sound energy that moves to a ceiling and comes back down may die too suddenly.

Acoustic experts disagree about whether pew or chair cushions are an advantage. On the one hand, rooms have longer reverberation periods when empty than when occupied. Sound dies faster when there are many people in a room because they absorb sound. And this discrepancy between a full, half-full or an empty room can make a troublesome difference in hearing. Seat cushions on empty seats absorb some of the sound a person would, but when people are present, seated, the cushions are covered and they do not affect the overall absorption. Thus the difference in the sound between a full and an empty room is minimized, and this is an advantage. Some acousticians take another view: If people stand to sing hymns in a full house, the seat cushion is exposed as well as the total body, so the likelihood of too much absorption is inevitable. This issue may need to be resolved on the basis of other factors such as comfort or comparative cost.

In hymn singing, it is not important or possible that the words be articulated clearly in unison. So when we listen to an assembly singing hymns, we listen for music, rather than distinguishable words. This means there is a distinction from the condition desired for the spoken word and other sound sources. For the spoken word, the idea is to have near the source of sound a hard surface that supplies a first rebound at a very small interval, thereby strengthening and enriching the sound. Sometimes a lowered ceiling, a tester or a sounding board is useful if wall surfaces are not close by. For the sake of hymn singing, on the other hand, a high and spacious overhead where sound can move and mix is a great virtue.

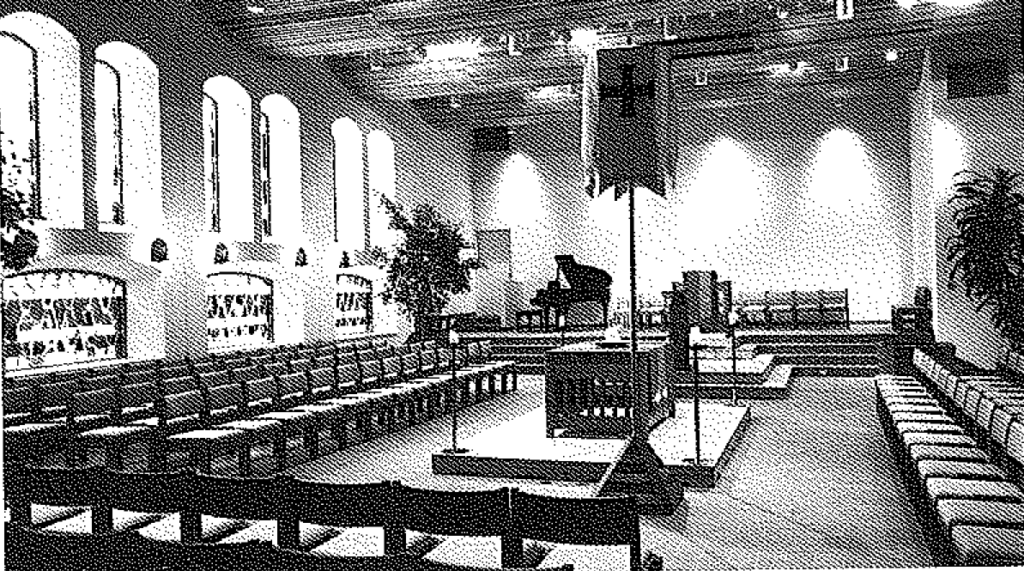

A built-in panel of breckwork backed with high-density fiberglass (above the window) is a better way of providing some absorption than adding on panels to the wall.

Obsorptive surfaces in this recital hall are kept to a minimum. But wall surfaces are given a complex topography to prevent flutter and diffuse sound.

This small room is ideal for hymn singing. The singers see each other. The ceiling diffuses sound as do both side walls.

The spacious overhead is good for all music. But there are a good many rooms that seem high because there is a high ridge beam or a tall peak. Some such rooms do indeed have generous volume, but some are deceiving. A typical “teepee” with an inside width of 50 feet, 10-foot sidewalls and a roof as steep as 60 degrees, rising more than 50 feet, will have an average vertical dimension of about 30 feet; but the volume of sound may be just marginally acceptable because too much of the sound that gets up into the space near the peak will never get back down.

It is usually required that sound absorption be supplied at wall surfaces for the sake of other music and of speech; hymn singing is not likely to need it. All in all, the demands of a room in which to sing hymns are obvious, but there are a good many acoustics experts who tend to analyze church buildings as if they were concert halls or lecture rooms. They and architects may need to be reminded that hymn singing is something different and is a very important acoustical consideration.

An earlier sentence suggested that the resolution of the tension that exists between acoustics appropriate for speech and those best for music generally results in a considered compromise in design. Some decades ago, acoustics problems often were solved by mounting sound-absorbing materials in great quantities on walls and ceilings, and then blasting into this dead space with loudspeaker systems for the spoken word, and sometimes for choir and organ as well. The result is deadly for music and for hymn singing, and in addition, it often supplies an electronic distortion to speech that is a sort of veil between speaker and hearers.

Few acousticians would propose such a prescription anymore; dead rooms are abhorrent, so flutter, echo and other acoustic ills are dealt with in much more sophisticated ways. But sometimes a very generous reverberation period is supplied for the sake of music, and the assumption is made again that a good public-address system can make speech easily intelligible by projecting selected frequencies into a very live space. This does not always work. Sometimes the space can be too live and speech can be understood only by straining. Almost inevitably speech is distorted, and the question must be asked: If it is important that music be heard well and without electronic distortion, is it not equally important that speech be heard without electronic distortion? The point of compromise—the need for an intermediate reverberation time—should be a matter clearly understood by the members of the church and by design professionals.

**A note from the Director of The Center for Congregational Song: This article, from 1990, contains a lot of great wisdom and advice on architecture and acoustics for hymn singing (which is why we re-posted it). However, it also is assuming acappella or acoustic-instrument led congregational singing. The addition of electronic/amplified sound is not addressed and certainly needs to be! We are currently seeking an author who is knowledgeable about architecture/acoustics and passionate about congregational song to write a followup article on that particular issue.