I started a new job this semester.

I now serve part-time as Director of Music for the Anglican Studies program at Saint Paul University. Anglican Studies is less of a stand-alone program and more of a collection of courses, workshops, and community-building activities to support Anglican students studying at our Roman Catholic institution.

Many of them are pursuing ordination within the Anglican Church of Canada, so we hope to form them in ways that will enrich their future ministry. My primary task is selecting and leading music for weekly Eucharists.

This new role has invited me to reflect on the “denominationally promiscuous” character of life as a church musician. I am Mennonite, not Anglican, but I regularly lead music in an Anglican setting and teach our students how to do the same. It has been a strange season of “faking it”:

- In this role, I try to model confidence in the role even as I regularly make mistakes and learn more about the Anglican tradition. For instance, did you know that Anglicans—or, at least, Anglicans in Ottawa—often chant the Sursum Corda (“The Lord be with you” / “and also with you” etc.) and opening preface of their eucharistic prayer, then sing a setting of the Sanctus (“Holy, holy, holy Lord” etc.), but then speak the remainder of the prayer? That was confusing for me.

- Each week, I try to select and lead music in ways that suit the rhythms and ethos of Anglican liturgy even as I bring my Mennonite assumptions to this role. For instance, the cohort of Anglican students is quite small, which means that it is best for us to repeat much of our repertoire from week to week to build confidence. That feels different from leading music in some Mennonite contexts where worship is characterized by a sense of novelty, making it difficult to repeat the same song for more than a couple of weeks at most.

- For the most part, our Anglican liturgies follow the Book of Alternative Services verbatim. For this reason, when I am introducing a song in an Anglican context, I tend to limit extemporaneous verbal instruction to one sentence—or, if possible, I don’t speak at all, instead inviting the congregation to sing with me through physical gestures or an instrumental cue. Once again, this manner of leading a song is different from what I encounter in some Mennonite contexts, where it is more common to share a brief verbal reflection on a song and provide specific instructions (e.g., “We will skip the third verse” or “Please rise to sing”) before singing it.

As I come to the end of my first semester in this role, I am reflecting on the last three months while also looking ahead to the rest of the academic year. I have already learned a lot, but I continue to wonder: How should I approach leading music in the context of someone else’s tradition?

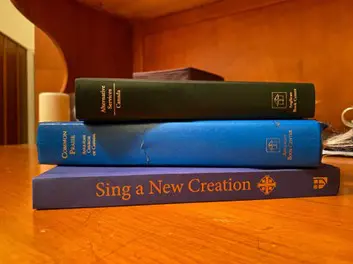

I have found it helpful to draw from my experience as a qualitative researcher to develop a twofold answer to this question. Qualitative research often involves entering spaces where you feel like an insider and an outsider at the same time, seeking to learn from the people who are already there. In these situations, I try to remember, first and foremost, that it’s not about me. Even if I hold a leadership position among Anglicans right now, I am not the authoritative voice on how Anglicans worship or what they sing. Leading well as an outsider requires deference to people with a deeper understanding of Anglicanism, making use of the resources that are most familiar to them—including hymnals, of course, but also extending further to psalm tones, singing bowls, unspoken cues, and whatever else might sustain their musical tradition. It would be inappropriate to impose my Mennonite habits and assumptions on this existing musical culture.

At the same time, as a qualitative researcher, I recognize that I am not neutral. I bring my Mennonite identity into this Anglican space. I cannot set aside the values and experiences that I carry with me from another tradition, nor can I help it when I feel confused or frustrated by aspects of the Anglican tradition that are unfamiliar to me. The task thus becomes choosing how to manage and share these parts of myself with my Anglican peers in a way that fosters mutual learning and appreciation between us, and, most significantly, equips them for effective leadership in their respective Anglican communities:

- Sometimes, that means quietly acknowledging to myself that my approach to leading a song two days ago at a Mennonite church will not transfer well into today’s Anglican context, so it is best to adapt my methods and see it as an opportunity to learn something new.

- At other times, I might be too quick to assume that what worked in a Mennonite context can easily transfer to an Anglican context, forgetting that I sometimes need to make tweaks. For instance, there is a song that we often sing at our weekly Eucharist with a slightly different melody than the version that I first learned in a Mennonite context. I have therefore started to lead the song on a couple of occasions according to the melody that I know best, which has required me to stop and start again with a soft smile. These moments of vulnerability are just as formative and enriching for my Anglican peers as the moments when I lead them without making any mistakes.

- Lastly, and only occasionally, there are times when it can be helpful for me to take some aspect of musical leadership that I learned in Mennonite communities and use it to enhance the way that I teach and lead our Anglican students. Just as I am finding that Mennonites can learn a lot from Anglicans, there are moments when I can suggest (with or without explicitly saying so) that a Mennonite perspective on some aspect of musical leadership can supplement what Anglicans already think about it. I see these moments as the exception, not the norm.

It is such a privilege, even if challenging at times, to serve in a role that is tied to a robust tradition that is not my own. Receiving a warm welcome from this year’s Anglican Studies cohort has positively shaped this transition for me. In turn, it is my task to support them, to the best of my ability and experience, as they lead their communities into ever more faithful understandings of what it means to be Anglican. Music is the way that I both serve and learn from them on this journey.

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration and a Master of Theological Studies. She obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada. Currently, she is a PhD student in the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, ON. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She also co-directs Ontario Mennonite Music Camp and chairs the team of volunteers who maintain Together in Worship, a curated collection of free worship resources from Anabaptist sources.

Mykayla Turner holds a Master of Sacred Music with a Liturgical Musicology concentration and a Master of Theological Studies. She obtained her A.C.C.M. in Piano Performance from Conservatory Canada. Currently, she is a PhD student in the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, ON. Apart from her academic work, she is an active church musician and liturgist. She also co-directs Ontario Mennonite Music Camp and chairs the team of volunteers who maintain Together in Worship, a curated collection of free worship resources from Anabaptist sources.

Learning from other Christian traditions is one great way of expanding your understanding! I’m sure you and those you lead are expanding in good ways.